Alaska’s Iron Dog 2010

World’s longest snowmobile race.

The first Iron Dog event started in 1984, in Big

Lake following the Northern Route of the Historic Iditarod Trail to Nome.

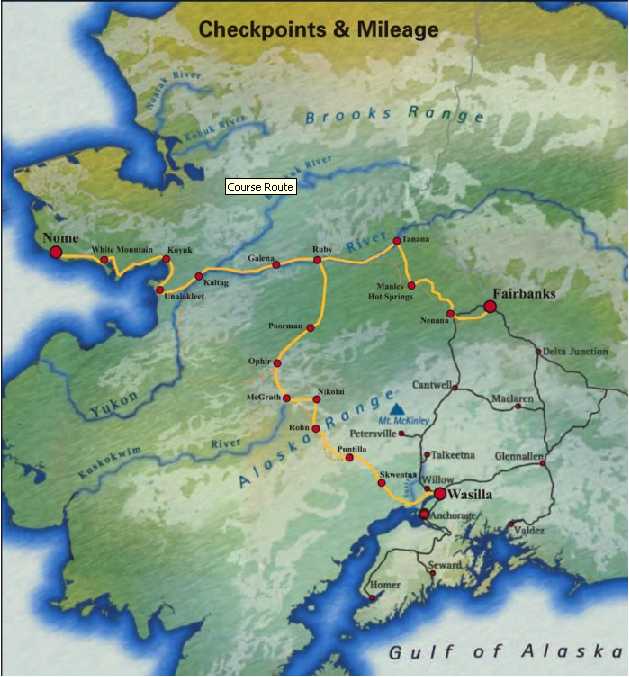

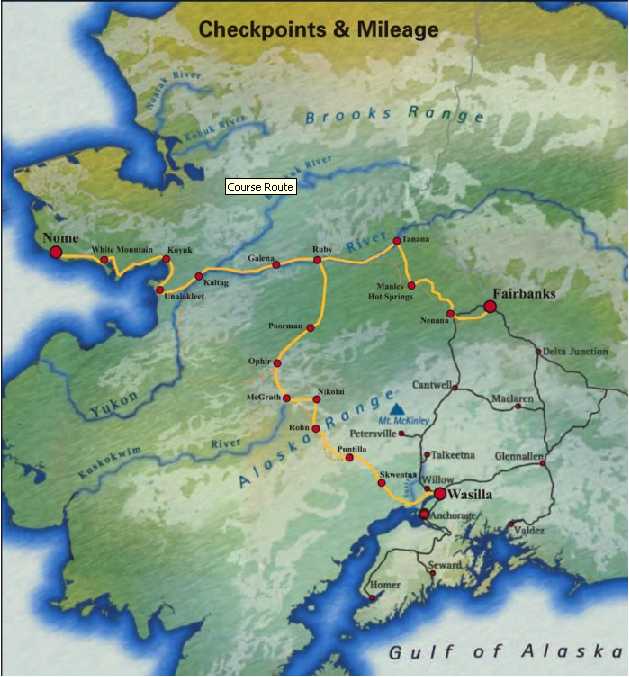

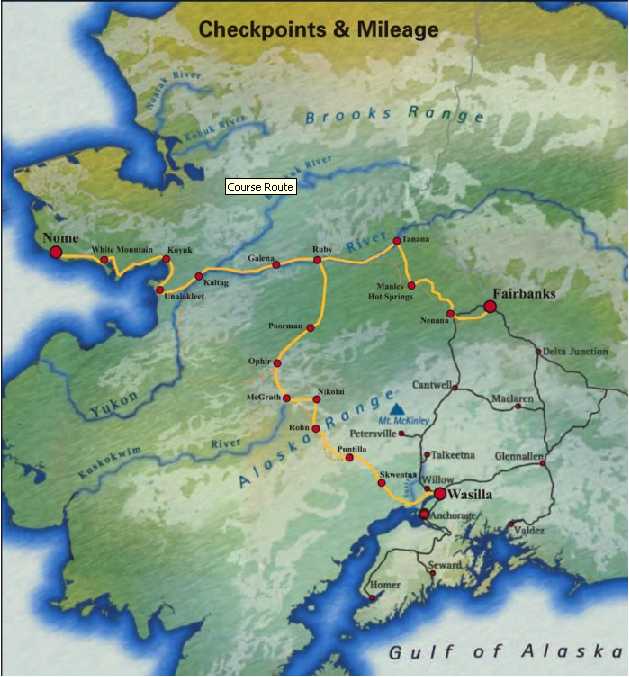

Today’s Iron Dog course length 1971 miles,

starting in Big Lake to Nome and finishing in Fairbanks, making it the World’s

longest snowmobile race.

The Iron Dog offers a non-competitive

recreational class & the Pro Class Teams.

Iron Dog Blog http://irondog2010.blogspot.com/

To get all the info go to the Iron Dog Website. http://irondog.org/

A friend of mine Frank Mielke from Chugiak

participated again this year in the Recreational Class.

He participated as one member of team #46 Team Black & Blue

He wrote the following story after his

return to Chugiak.

IRONDOG 2010 TRAIL

CLASS: ROUGH COUNTRY FOR OLD MEN by © Frank

Mielke 2010

But Rain, Bare Ground,

Open Water and Engine Failures Can’t Keep Team Black & Blue from the Finish Line

in Nome.

“Well, I can tell this is going to be an adventurous ride,

with lots of stories out of this by the end of the trail” I said to my wife Shelley. In three hours we would start the Trail Class of

the Irondog, the “World Longest, Toughest Snowmobile Race”, two days before the

Pro Class start. I claim no gift of prophecy. But the conditions, mainly the warm weather, and

reports of no snow on the Farewell Burn, promised more opportunities for a more eventful

ride. Having a team of 6 riders meant we

should have about the same amount of calamities as three 2-rider teams. We would be crossing the Alaska Range, three

distinct climate zones and the Susitna, Kuskokwim and Yukon drainages, which cover the

majority of the land mass in Alaska. Anything can happen on the Irondog. This year 38 riders were in the Trail Class, twice

as many as some previous years. The field

included many veterans who had run the Pro Class. That

too would help make it an interesting run.

Whatever the condition,

once you are committed and ready

to go, there isn’t a thought of not running, unless the race itself is cancelled.

But to

explain why we were running in the first place, well, it’s just about the grandest

adventure that a regular guy can do. There’s

simply nothing like it in the world. We had

already gotten the Irondog bug, as all but one of our team ran together in 2007 or 2008. We watched the 2009 start, and the envy was

obvious. All my former teammates admitted

some degree of regret. Each of us started

thinking about running again right then and there, if we hadn‘t already.

So we formed a team, called Team Black & Blue, the

colors of the Ski Doo Summits four of us were running, and the color of our bruises by the

time we would reach Nome. Our team roster

read like this:

Larry Weisheim, age 68, 5th Irondog, Anchorage

Gene Tharpe, age 71, 1st Irondog, Bradenton, Florida

Bill Mielke (my brother), age 61, 3rd Irondog, Wasilla

Frank Mielke, age 60, 3rd Irondog, Chugiak

Otis Mielke (Bill’s son), age 32, 2nd Irondog,

Wasilla

Tim Bruns, age 47, 3rd Irondog, Wasilla

If Gene finished, he would be the oldest finisher in Irondog

history. Again, as in 2007, we would be the

oldest team (totaling 339 years), running long track sleds, the slowest in the field. I also predicted that our long tracks again would

be required to break trail somewhere, as we had done in 2007 and 2008. Again, this was no mystic prophecy, just a

statistical likelihood under such conditions.

The temperature at the start was over 60 degrees warmer

than it was on our last run in 2008. Imagine

how different LA is at 20 degrees than at 80 degrees and you get some idea how drastically

different the issues can be. It was more than

70 degrees warmer in some spots upriver. The

temperature, just above freezing, rose slightly and within 10 miles rain started. And it would rain or snow all the way to the first

layover. This didn‘t dampen any spirits.

After the first checkpoint at Skwenta, most of the teams

stopped at Shell Lake Lodge, the second checkpoint. We

went past, and teams started following us as we prepared

to “climb the stairs” over into the Happy River Valley and into the Alaska

Range. About 30 miles from Puntilla, the

third checkpoint, we met the trail breaking team, who went ahead, following a GPS track

from a previous year’s race route. There

isn’t just one Irondog route, as trail locations are often changed to meet changed

conditions.

There was about two feet of fresh snow, that covered most

of our tracks from a training run the week before. However, the GPS route had not be used

by teams training for this year’s Irondog, and the snow lacked any packed base. Machines that spun sank quickly and were difficult

to extract. It was impassible in such rainy

conditions. The entire trail class waited

behind the trailbreakers until thoroughly soaked. They

couldn’t seem to make much headway, so we decided to take the trail we

trained on. Our odds looked better if we went that way. Now,

turning around in a single file trail with five feet of sticky snow on each side is no

easy task. Machines needed help getting

turned around. Chris Maynard, a most expert

snowmobile guide and trekker, suggested we “foot pack” the steep hill on our new

route. About half the trail class riders

pitched in and sweated their way to the top of the hill packing a better trail, and Otis

and Bill and I drove our machines up, breaking a new route around the problem area. All followed our packed trail, including the

trailbreakers.

We made it to Rainy Pass Lodge late at night, soaking wet. The entire trail class, minus two who stayed at

Shell Lake, overnighted there. Our lodging,

which we shared with about three other teams, was draped with soaking wet gear. The weather cleared late at night, and the second

day promised to be a better day. But nothing

is guaranteed in the Irondog.

We left the next morning to much better weather, but still

too near the melting point. We were one of

the last teams out, and followed tracks to

Hell’s Gate and the South Fork of the Kuskokwim River, which empties into the Bering

Sea. We made good time toward Rohn. I failed to notice open water in time and spun

wildly to get across, which I did, but my machine spunout of control when I hit the ice on

the other side, It flipped and broke the

windshield. It looked reparable, and we were

close to Rohn, so I stuck the windshield on the machine.

But it started to come off, and I didn’t notice that the track I was

following had been backtracked when the riders saw open

water. I tried to get across, the thin ice

broke, and in a flash I was in the water. My

first instinct was to get off the machine and out of water.

I jumped off quickly and pushed back. The

machine was in the current, tipping over and about to be swept under the ice. My nanosecond thought was, without my machine and

gear, I’m not much good back here. I’ve

got to save the machine. I found a place

where I could stand, grabbed the handlebar and righted the machine, which still had some

flotation and strained to pull it away from the current.

Next, I pulled my tow rope out of the handlebar bag, and

looped it around the mountain bar on top of the handlebars and threw the rope to Larry up

on the bank. We held the machine until Tim

and Bill got ropes around the skis hooked up to their machines. I pushed a large chunk of floating ice up to the

edge and used it as a ramp and Bill and Tim pulled the machine out. I was in the icy water for over 10 minutes. I got out of my wet clothes, and got covered

quickly. I had heard that you can fill your

bunny boots (rubber military boots, worn by most Irondoggers) with water, dump the water

out wring your sox out and put the boots on and keep your feet warm. I didn’t really believe it, but I do now. I managed to get dry enough to keep from shivering

too hard, and Bill started towing me to Rohn. It

took three machines and considerable hauling to get mine up a steep riverbank and into the

Rohn checkpoint.

Fortunately, there is a warm cabin at Rohn. While I was

warming up and drying out, Otis, ace mechanic, went to work. He had it running before I was dry. The firing of the engine was one of the most

beautiful sounds I’ve ever heard. We

were on the trail out of Rohn and though almost everyone had passed us by then, we only

lost about 2 hours. Bill said it was akin to

an Old Testament miracle. With no

carburetors, and a totally sealed electronic

system, there isn’t a lot to get wet. Shutting

the engine off early was critical too. I

couldn’t believe my luck (or my stupidity for being in the water in the first place).

But now we faced the Farewell Burn, usually the roughest

part of the trail. Reports were bad, terrible

in fact, and horribly true. It took us about

9 hours, instead of the 2 to 3 hours it took us in 2008.

That‘s 9 backbreaking, bone jarring, exhausting hours instead of 2-3

hours of sit-down riding. I‘m never sure

of the exact time across the burn when it is rough, because you have to ignore time. I say, don‘t look at your watch, don’t

look at your odometer, it’s much too discouraging.

Keep in mind if you keep moving forward, you will eventually get though.

The Burn in 2007 was just as rough, except the rough part

started to fade about 20 miles out of Nikolai, and got better with more snow as we went. This year the rough terrain attacked you with its’ relentlessness,

fighting you all the way to the river at Nikolai. Only

then did we had good snow. About the only

smooth surface we had was the lakes, which were thawing in the warm weather, and we had to

skip across open water on most of them. Open

water made me understandably nervous at this point. When

the engine speed increases and the vehicle speed decreases, no matter what you are

driving, the instinct is to feather the throttle to get better traction. When crossing open water, one must fight that

instince and squeeze the throttle harder when the track spins. Only later did I wonder what would happen if your

engine quit in the middle of the lake.

We passed two teams having mechanical problems on the Burn,

so we felt we were finally getting back into it. We

made it to Nikolai at 11 PM. We had intended to go on to McGrath, but

considering what the day had been like, we accepted the invitation to stay in Nikolai,

which previous Irondoggers had passed on. We

stayed in the school gym and slept well on the tumbling mats. The locals cooked us dinner at midnight and

breakfast in the morning. The people of

Nikolai couldn’t have been nicer. It’s

not the competition, but the camaraderie and good will that make the Irondog trail class

run a tremendous experience.

We made good time into McGrath and several teams were still

there, others having just left. A checker at

Rohn had called ahead and had a windshield waiting for me.

It wasn’t an exact fit, so I put it on with Larry’s Gorilla tape. We greased our machines and were off again. It was fun to run in the pack again. The trail to

Takotna was good, but then again, after the Burn everything seemed pretty good.

From Takotna the route follows a summer mining road, with a good

surface, and is one of the most enjoyable stretches of the Irondog. It is uphill as it goes out of the Kuskokwim

drainage and up over into the Yukon River drainage, in the Innoko River Valley. We made good time in the almost 100 mile run to

the ghost town of Ophir. This part of the

Innoko valley is almost a dead zone. A miner

told me that human artifacts or old animal remains or fossils are only rarely found in the

thousands and thousand of yards of gravel mined for Gold in the Innoko District. Animal tracks are sparse and it looks very dry. Maybe that’s why no one lives in the almost

250 mile stretch between Takotna and Ruby. But

it was beautiful in its starkness and unusual light as the daylight faded. We encountered rain again, but it was light and

transient. We made good time to Poorman,

another mining town turned ghost town.

Poorman is always a

welcome checkpoint, and even better this year, with the Army National Guard, the prime

Irondog sponsor, furnishing a tent with life phone and computer connections. We called home and enjoyed the perennial hot stew

and powerade furnished by the Spenard Builder’s Supply volunteers. We felt good as we departed for Ruby, 57 miles

away. Most of the teams were bunched up at

Ruby with a couple further downriver. We

stayed at Rachel’s B & B, where we had our best meals on the trail. Who would expect

chicken parmesan late at night in Ruby? We

left well rested in the morning, finally ahead of most of the trail class teams. The Yukon River was generally smooth and we

blasted to Galena and on to Kaltag.

At Kaltag the trail

leaves the Yukon and goes over via an ancient trade routes between Indians on the river

and Eskimos on the Bering Sea coast. We heard

horror stories about the rough trail from

Kaltag and no snow in the Unalakleet Valley. The

trail was a little rough, but improved and was very good and well marked into Unalakleet. The ride in was spectacular and we met many of our

trail class friends. Rooms were scarce there,

so we proceeded on to Shaktoolik, a beautiful 40 mile ride along the coast in the fading

light. We found a rare exception to the usual

generous rural Alaska hospitality in Shaktoolik, getting a meager dinner of a bologna sandwich and cup of noodle soup, and

breakfast of toast and coffee, which we paid dearly for.

Leaving Shaktoolik, we had moved up to third place and felt

pretty good. We left around 8 in the morning

and about 20 miles out Bill’s engine burned up.

I towed Bill into Koyuk, approximately 40 miles, and Otis worked on the engine. He got it running on one cylinder, good for about

40 mph. It lasted about 20 miles and quit for

good. Otis towed Bill the rest of the way to

Nome, about 135 miles.

But we still made

good time, towing at 30- 40 most of the time. We

proceeded mostly on ocean ice to White Mountain on a most beautiful and sunny day. We went past Elim and Golovin and crossed Golovin

Bay, then up to the Fish River to White Mountain. The

local volunteers at the checkpoints were great, helpful and efficient. Just past White Mountain Tim saw a guy fishing

tomcod through the ice and we stopped and visited, and Tim fished for awhile. It’s the things along the road that count not

the road, I was once told. Three different

riders told me they wished they had stopped more, taken

more pictures and taken more time to visit.

I recommended they do the Irondog again

so they can truly enjoy the ride.

Five miles out of

White Mountain, my engine burned up. As it

turned out, a majority of machines running 2010 e-Tec

engines had engine problems. Larry towed me

the 75 miles to Nome. But it was warm, I

never got cold and we made it to the finish line, dubbed “Team Black & Blue,

Towing Two” but beating the first racing team into Nome. We spent two days in Nome. One needs a couple days to decompress and realize

that there is another world outside the Irondog. And

Nome is a great town to hang out it anytime.

There are always

lessons to be learned, noted and reinforced from experiences, like the Irondog, that ride

a fine line between fun and disaster. One

I’ve noted, but still don’t always observe is: take care of your little problems

so they don’t grow into major problems/stop and fix your windshield so you can focus

on the trail. Also, keep your tow rope handy. I would have lost my machine for good if I

hadn’t been able to get at my strap pronto. The

rules required one tow rope per team; we had one per person and needed all of them. A pro team had to go an extra 50-60 miles to get a

second rope to tow into Nome. Another pro

team lost a machine in Norton Bay and a handy tow strap might have improved their odds of

saving that one. But the best lesson is there

are no winners or losers in the trail class. I’ve

never seen an event with so many competitive people who got along so well. That is probably as remarkable as the terrain, or

the scenery, which is truly spectacular. We

started friendly and ended as friends.

It’s been said

that in the Irondog, any finish is a win. We

had a great time, and no one questioned if the effort was worth it. It is truly a world class adventure. Where else but Alaska could a regular guy of

normal means participate in the premier event of its sort in the world? We‘re the luckiest people alive, and given

what I went through, I’m among the luckiest of the luckiest.

Back To Snomobile Page

Back to Chugiak, Alaska Page